Zen & The Carnivore Diet

Steak dinner in Phoenix.

Meat...

Since I left Oakland last month, I began a carnivore diet. My brother had been touting its benefits since he lost twenty pounds in the first few weeks and felt like, how did he put it, he was “twenty years old again.” His energy was up, he was eating less, spending less time cooking (useful for those with children), and the old libido was back. For an introduction, listen to the episode “The Carnivore Diet” on his podcast, Move with Motus.

I didn’t expect to like it as I’m a bit of a vegetable man. I had been vegetarian several times in my life and preferred, always, a mushroom, a leafy green, a nice baguette, a stinky cheese, anything really over meat.

I arrived at my friend Chris’ house in Phoenix a few weeks ago and told him—warned him really—that I had just begun an obnoxious meat diet and would only essentially be eating meat, fish, and liver. I had checked out Paul Saladino’s (self-described “leading authority on the carnivore diet”) article entitled: “What to Eat on a Carnivore Diet. Your Carnivore Diet Meal Plan!” before beginning along with his interview with Joe Rogan.

Paul Saladino divides the diet into five variations, or tiers, of the carnivore diet that you can choose from depending on your goals. The first, where I began, allows for a few non-meat items: cucumber, lettuce, olives, and avocado, which are described as “low toxicity plant foods.” Everything else is meat, and most importantly, grass-fed meats (typically on the bone) and occasionally, organ meats. Tiers 2-5 become incrementally intense ending with raw eggs and liver, beef suet, and testicle. Yes, testicle. So I largely stuck with tiers 1 and 2.

As explained in Saladino’s book, The Carnivore Code, the philosophy seems to boil down to these two concepts…

1 - “Animal foods are the most nutrient rich nourishment on the planet…”

2 - “Plants exist on a spectrum of toxicity and contain defense chemicals (phytoalexins) that may be damaging and toxic for many individuals. In order to survive their co-evolution with animals, insects, and fungi over the last 450 million years, plants needed to develop chemicals that protect them from unabated predation. For many people, elimination of some or all of these chemicals will lead to a higher quality of life.”

Sure. I’ll try it.

The initial week was unsettling. I only really wanted two meals per day, which inadvertently led to intermittent fasting, an important part of the diet that I had really only glanced over. I had been used to waking up, eating immediately, three meals per day, and stuffing my face continuously throughout the day with snacks.

It was an unexpected realization that my relationship with food had become more or less an activity that diverted my attention from more serious concerns, mainly, creative activities. Instead of writing, practicing guitar, design, whatever it may have been, I would make tea, eat more dates and dark chocolate, plan, shop for, and cook another elaborate meal. My entire life had been that way: concerning myself with my next meal instead of working towards my goals. Fascinating.

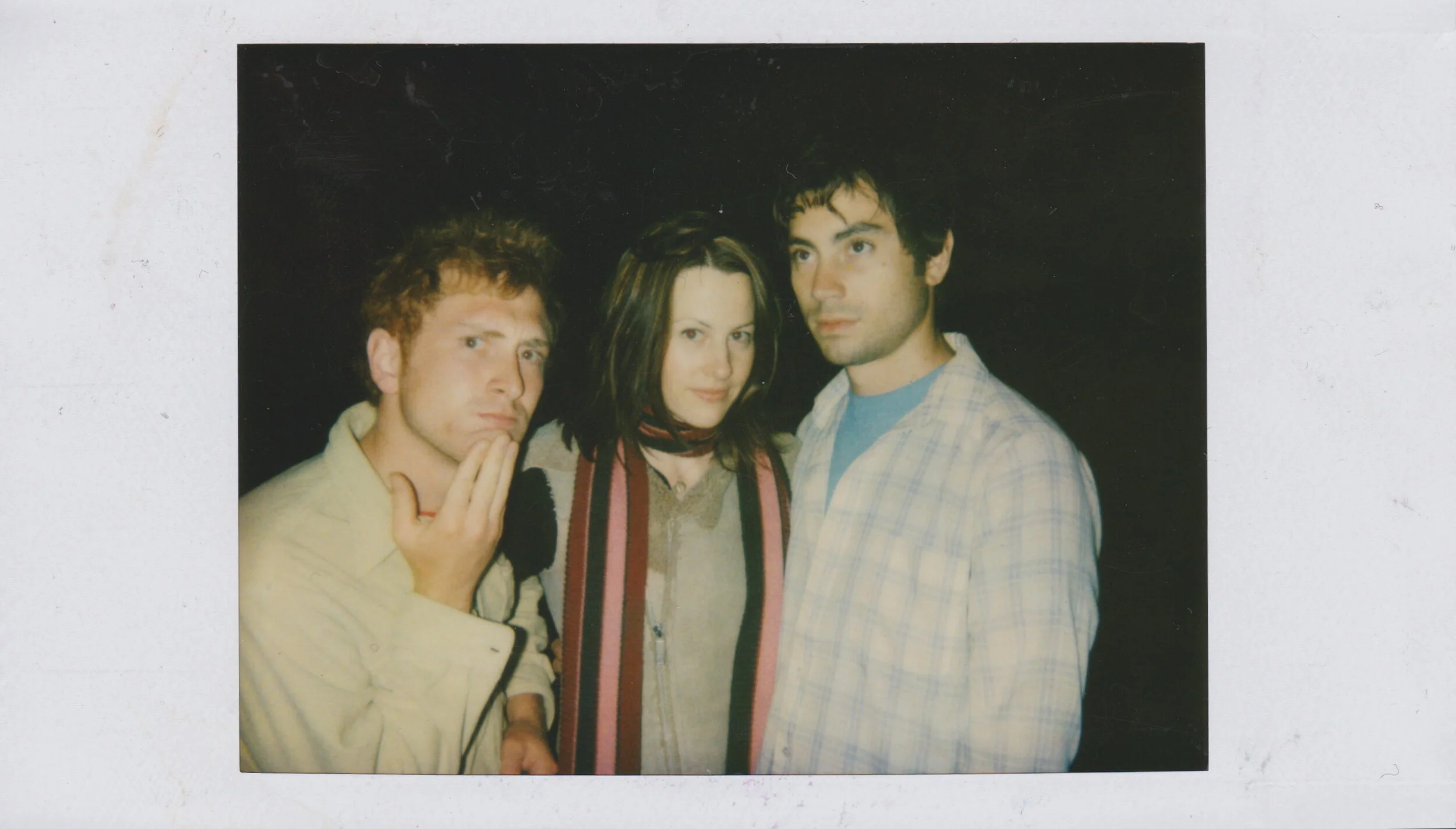

My first days of Zen. 2018.

Three years ago, after a much needed break from the world of tech and staring at computers, I moved to a Zen monastery in the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico (the above photo is actually in Colorado where I often had to go to pick up one of the Zen teachers). On the first evening that I had arrived, we ate at a restaurant across the street, a roadside diner with a rundown lodge atmosphere. There were a few locals at the bar drinking heavily on tree trunk stools under a wall of dead animals. Our small group was a collection of pale and exhausted looking monastics that the townies were apparently used to seeing. They paid us little attention and stared at either their drinks or the television.

We sat at a long table near a wood burning stove and considered the menu, which largely consisted of meat and more meat. The head abbess ordered a steak that barely fit on the plate along with a few glasses of wine. It was quite the introduction to Zen as I had been under the impression that all Buddhists were vegetarian and sober. Apparently, this was a capricious crew of spiritualists.

I had arrived as the head cook, or tenzo as the position is called, with the intention of really only spending my days in the kitchen, doing a little meditation here and there, and soaking in the hot springs (image at the top of the post) behind my room. Those intentions, however, were quickly diverted when it became clear that the majority of my time would be spent in the meditation hall.

The average day was about four hours of meditation and during retreat times, up to ten hours per day. Absolutely brutal, especially when you’re the tenzo, attempting to not think but having the responsibility of cooking three meals for up to fifteen people everyday. Every “sit,” as meditation is referred to as, only resulted in menu planning. After a month, I quit the tenzo role and become a full-time Zen practitioner and lasted for several months before heading back to my previous life, now a little different.

I left with a fairly decent meditation practice, the realization that living among people is…unpleasant, and finally, while the Buddhist scriptures say “to refrain from intentionally killing any living creature,” that many Buddhists are not in fact vegetarian.

My bedroom at the monastery.

There were of course other moments, self-realizations perhaps they might be called, that occurred, faded, returned, faded again. As far as I can tell, this is the way life seems to go and that there are many avenues one can take to improve and/or more deeply understand themselves through art, writing, relationships, therapy, meditation if you like. Maybe all of the above.

I’m not sure that the average person who intends to diet wants anything more than to look and feel better physically. Perhaps they’re also looking for mental and emotional clarity and, as Paul Saladino puts it, “a higher quality of life.” As strange as it is to say, the meat diet has certainly provided all of that. I sleep better, feel and look better, focus longer, and spend my time on activities rather than meal planning and cooking. Who knew that steak and eggs for breakfast would be a transformative experience.